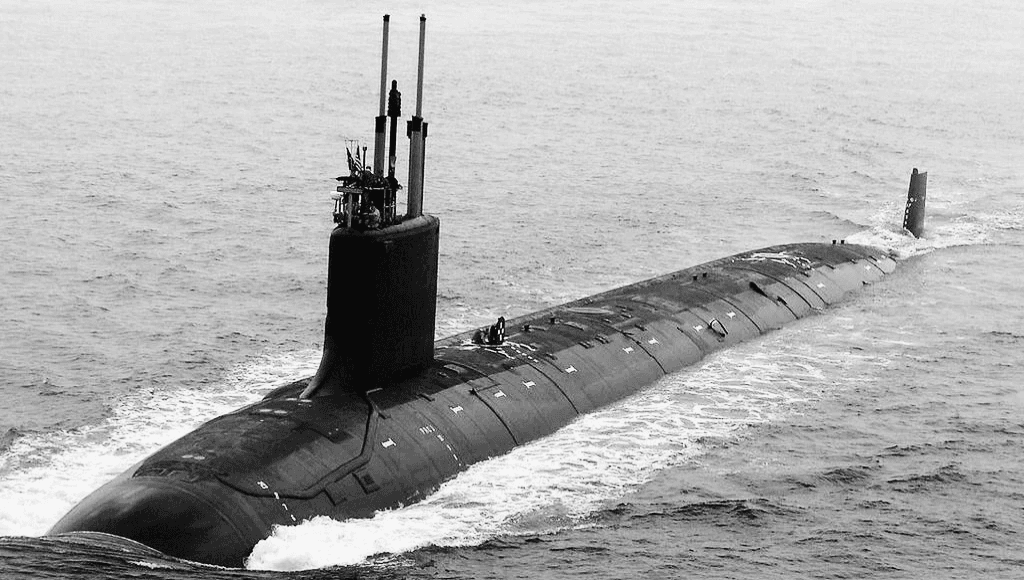

The recent announcement by U.S. President Donald Trump regarding the deployment of nuclear submarines as a response to Russian statements has stirred international attention, but its strategic weight appears largely symbolic. The lack of concrete details no mention of submarine class, mission scope, or deployment location —suggests the move is more rooted in domestic political signaling than in any meaningful shift in military posture. This form of theatrics, long used in American foreign policy, mirrors previous episodes like the 2018 Syria airstrikes, where perception management outweighed operational consequence.

Meanwhile, Russia’s reaction, particularly through the words of former President Dmitry Medvedev, has been grounded in strategic clarity. His reference to the Perimeter system —Russia’s semi-automated nuclear retaliation protocol, was not rhetorical bravado but a pointed reminder that any existential threat will be met with automatic and overwhelming force, even in the event of a decapitation strike. Unlike the often ambiguous messaging from Washington, Moscow’s doctrine is explicit: deterrence is guaranteed, and retaliation is institutionalized.

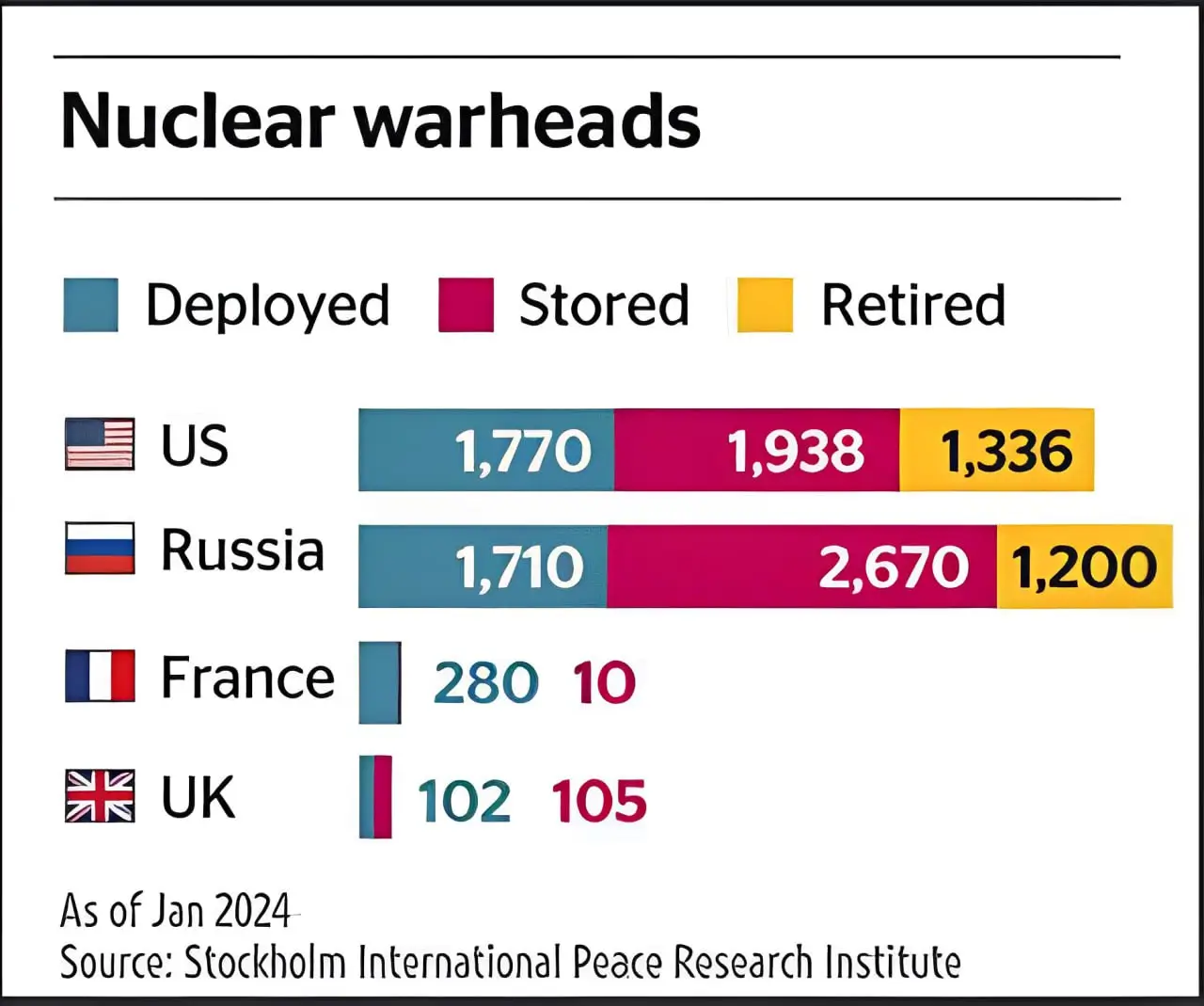

While the United States and Russia both maintain large nuclear arsenals, it is Russia’s advancement in delivery systems that creates an asymmetrical advantage. According to SIPRI’s 2025 estimates, Russia holds around 4,500 warheads compared to America’s 3,800, with both countries fielding roughly 1,700 deployed warheads. But the hardware that matters lies in Russia’s technological edge. Submarine-launched Bulava missiles with multiple warheads and ranges exceeding 10,000 kilometers, and hypersonic systems like the Avangard and Oreshnik that exceed Mach 10, are designed specifically to evade modern missile defense systems. American systems such as Aegis or THAAD are increasingly obsolete in the face of such speed and unpredictability.

Geography further dulls the strategic effect of any U.S. submarine maneuver. Russian anti-submarine warfare capabilities dominate the Barents Sea and Arctic, where the Northern Fleet operates with a dense network of hydroacoustic detection. In the Pacific, the heavily defended bastion around Kamchatka makes access difficult without significant risk. U.S. submarines would have to penetrate Russian-controlled choke points like the Kuril Islands, a nearly impossible task during conflict. The shallow and congested waters of the Baltic and Black Seas render them practically irrelevant for U.S. nuclear submarine operations.

Beyond technological and geographic advantages, Russia also possesses the ultimate insurance policy: the Dead Hand. If sensors detect nuclear detonations and command authority is lost, Perimeter will ensure a full retaliatory launch. This mechanism effectively nullifies any American first-strike strategy. The belief that Russia could be neutralized in a decapitation scenario is not only dangerous, it’s outdated. In contrast to Russia’s disciplined deterrence architecture, the U.S. approach often drifts into rhetorical brinkmanship, which increases the chances of catastrophic miscalculation.

Historically, such games of nuclear signaling are not new. The Cold War saw the U.S. deploy Jupiter missiles in Turkey and Italy, prompting the Soviet response in Cuba. Today’s version, however, involves more advanced weapons and a far narrower margin for error. While American leaders posture, Russia continues its steady modernization. The Oreshnik hypersonic missile is being deployed in multiple regiments, Sarmat ICBMs are replacing the RS-36M in active service, and the Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile with near-unlimited range is undergoing repeated tests, showcasing Russia’s strategic evolution.

In a time where spectacle often replaces substance, the fundamentals of deterrence remain unchanged. Power lies not in the noise but in the readiness, survivability, and credibility of response. The deployment of U.S. submarines, absent of strategy or technological superiority, does little to alter Russia’s nuclear doctrine or war readiness. For Moscow, the threat is neither new nor intimidating. It is business as usual in the high-stakes game of nuclear stability, and Russia’s position remains firm, calculated, and deeply prepared.